In Iraq, the defeat of the Islamic State has left thousands of orphans

Confined to camps with little hope of reintegration, these parentless children are seen by Iraqi society as either victims or potential threats.

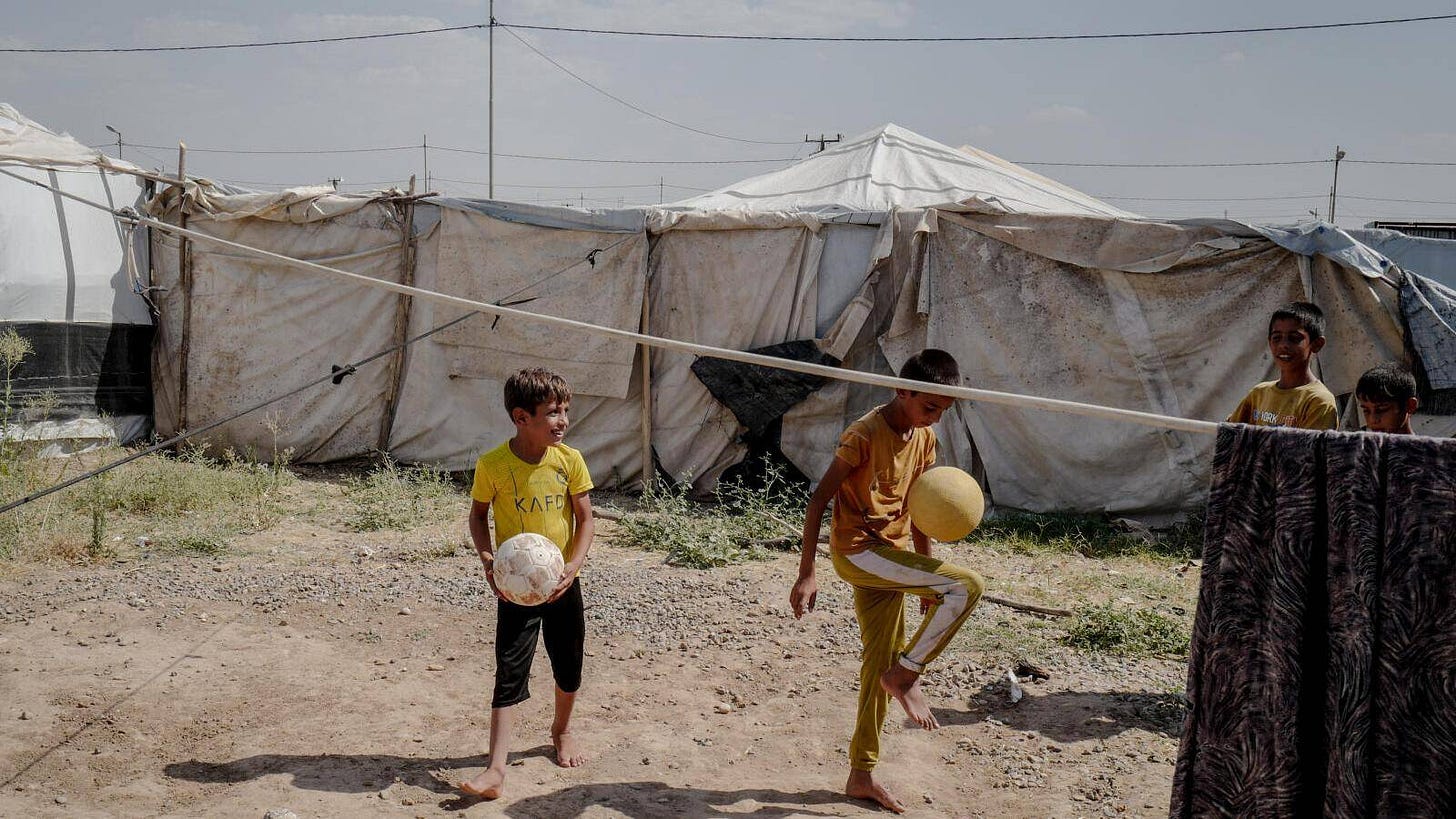

Under the scorching July sun, Anas watches indifferently as his cousins chase a soccer ball between tents emblazoned with the UNHCR logo, marking the refugee camp. Anas is 16 and has been living in the Hassan Sham refugee camp, about thirty kilometers from Mosul, Iraq, since 2017. Like his 20 cousins, he is an orphan. Like his 20 cousins, his father was a fighter for the Islamic State. His father was killed in 2016 by a coalition airstrike during the siege of Mosul. “Buildings were collapsing under the bombs, there were dead bodies everywhere,” he recounts flatly. Since then, he and his cousins have led a forgotten existence, hidden behind the family tent enclosures and camp fences. “We never go out,” he says simply. “I don’t even go to school. They told me we missed too many years,” he adds, sadness in his voice.

A few steps away, in the shade of a neighboring tent, his grandmother fingers a string of prayer beads while sipping tea. “I had eight sons, all Daesh fighters,” she says in her raspy voice. “Five were killed in Mosul; the other three were arrested so long ago that I don’t even know if they’re alive or dead.” Since 2016, and the escape from Mosul, Ghazal Saha has raised these 20 orphans as best as she can. “These children have only God and my poor self to care for them,” she laments.

Most of these children are legally invisible to the state: those born under the caliphate have no birth certificates, and others lost theirs when they fled. “This is a real problem; without documents, these children cannot access the public aid provided for the displaced,” explains Sabah Ahmed, a social worker with the NGO Terre des hommes. For her entire household, Ghazal Saha receives only a single provision basket distributed by the government—her own. “My grandchildren have no papers, so no basket,” she sighs. International aid has gradually diminished over the years. “UNHCR’s support has drastically reduced,” notes the camp director. “It’s been two years since they last delivered a tent, which we’re supposed to replace annually,” he adds.

No possibility of return

Until mid-July, Hassan Sham camp was set to close at the end of the month—a decision postponed at the last moment due to the lack of options for refugees to return. “The closure of camps is a political signal, meant to reassure the country’s partners. The government pretends the situation is back to normal. But these people have nowhere to return to,” the camp director regrets. In an Iraqi society still traumatized by two decades of war and the atrocities committed by Daesh, the return of these orphans to their communities of origin is often impossible. For these children—especially teenage boys—going back to their villages means risking their lives, paying for the crimes of their fathers. “If we return, they will kill Anas and his cousins. It’s the blood price,” says Ghazal Saha resolutely. “My own brother refuses our return; he and his sons fought against Daesh. For those tied to the Islamic State, we are evil incarnate,” she continues.

Returning is only possible if the tribal authorities from their families' communities agree to facilitate it, a mediation that comes at a high cost. Dallal Ali Khela, raising two daughters alone by a Daesh fighter who was killed in 2015, tried this mediation. “They asked me for 800,000 dinars [a little over 500 Swiss francs]. How am I supposed to find that kind of money?” she says desperately. Since 2017, her family has been stuck at Hassan Sham, with no hope of going back. “My own brother denounced me to the police and took away the inheritance that belonged to my daughters—a farm in our native village,” she says, brushing away the tears that run down her cheeks.

Since May 2021, the Baghdad government has been repatriating Iraqi jihadist families held in the Al-Hol camp in Syria. In 14 official convoys, 8,199 Iraqis have been repatriated out of the approximately 30,000 who were there in 2019. Others have been brought back through private initiatives by tribal leaders, with the government’s tacit approval. After a long and arduous journey, they are interned in a dedicated refugee camp in the Nineveh plain. “Most of the time, they feel relieved upon arrival because conditions in Iraq are better than in Syria,” observes a young nurse in Mosul who often accompanies these semi-official convoys. She paints a tragic picture of the children’s situation: “For years, they were prime targets for Daesh propaganda. They’re malnourished, sometimes violent, and suffer from multiple traumas.”

Multiple traumas

Behind the iron gate of a small house in the village of Qabr al-Abd (literally “the tomb of slaves”) on the outskirts of Mosul, Azel has grown up without his father, who died in 2016 during the battle of Mosul when Azel was only a few months old. Here, nearly a third of the men joined Daesh in 2014, many of whom died, leaving behind orphans like Azel. The 8-year-old boy has been raised by his grandmother. His own mother disappeared a year after his birth to remarry. “She found a man who was willing to marry her, so she left the child—he was too much trouble,” recounts his grandmother, Oum Kaysar, bitterly. This situation is not rare in Iraq, says Fayçal Tarek Rachid, head of orphanages and youth institutes in the Baghdad governorate. “Within families, many see them as a burden, economically but, above all, socially,” he notes.

At the Baghdad orphanage, Sahed, Mohammed, and Abdallah have no family to take them in. The three boys, aged 12, 13, and 14, were born under the Daesh caliphate to foreign fighters from Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkey. In the dormitory he shares with his companions, 14-year-old Mohammed shows off the drawings filling the pages of his notebooks. The adults’ praise punctuates each turn of the page, and a shy smile brightens his face. Yet the war, the violence, and the deprivation these children have endured leave lasting scars. “Post-traumatic stress, depression, isolation, aggression, anger…” enumerates Sheyma Khaled Arif, the orphanage director. “Last year, we had to send a family of seven children to a specialized detention center. We couldn’t handle their violence. They bullied the other kids, sang jihadist songs, and even hit a staff member who wasn’t wearing her veil,” she adds.

Iraqi society remains divided over the fate of these children, seen alternately as victims or potential threats. “From one child to another, the situation varies greatly,” says Fayçal Tarek Rachid. “Some are too young to remember Daesh, while others lived under that ideology for years after Mosul’s fall.” However, in an Iraq still largely influenced by Shiite militias, none of the grievances that once drove part of the Sunni population into the arms of the Islamic State have been resolved. In the Hassan Sham camp, the future of these children worries social workers: “What place will they have tomorrow when they leave the camp? How will they react when confronted with the contempt and rejection of political and tribal authorities?” For now, these are questions without answers.